The young, single mother of a six-year-old was proud of the progress she had made.

Jasmine Williams, 29, had struggled with an opioid addiction for years. In March of 2021, Williams was caught by federal agents with illegal drugs and later that year pleaded guilty to federal charges in New Mexico.

During her sentencing hearing, Williams expressed optimism for her future. Yes, she would serve time in federal prison. But once her sentence was up, she would go back to school to pursue her passion and become an esthetician.

Williams, known by family and friends for her big laugh and kindness, achieved sobriety in the lead-up to her sentencing – and prosecutors recognized her progress. With no significant criminal background, US government officials recommended that she receive a reduced sentence.

According to her sentencing transcript, accessed by the Guardian, Williams promised the judge she would “make better decisions and go to school, and make a name for myself in a career that I actually enjoy, and take care of my daughter and set a better example for her”. The future was brighter.

Her mother, Tonya Petrides, shared that outlook.

“When you have a child who has struggled with addiction, you worry about them all the time,” Petrides said in an interview by phone from her home in Ohio. “She was getting better, so I wasn’t worried about her because she was getting better. She was optimistic. We had a plan.”

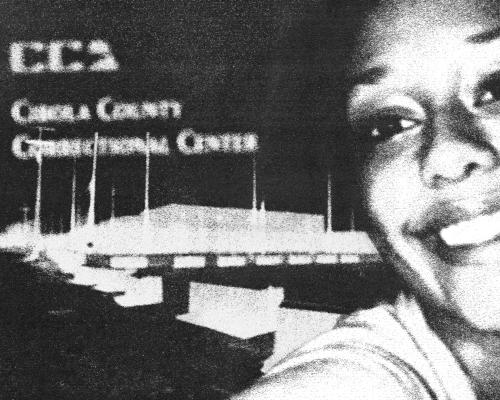

Two days after her sentencing, Williams turned herself in to the US Marshals Service (USMS) to begin her sentence and was booked into the Cibola county correctional center (CCCC), a privately owned federal facility in New Mexico.

The Cibola facility, run by the private prison company CoreCivic, houses USMS and local detainees, along with immigrants in Immigration and Customs Enforcement (Ice) custody. It has a problematic track record. An investigation by the Guardian has revealed that a disturbing number of deaths have been occurring at the prison, which is also under scrutiny by the FBI for what the agency has called an epidemic of drug smuggling there.

Williams is included in the death toll. Cibola was only supposed to be a temporary stop for Williams, who would then be transferred to a prison in Ohio to be closer to her mother and daughter.

But two days after being booked into Cibola, on 14 November 2021, Williams was found dead in her cell.

A medical examiner report obtained by the Guardian shows she died of an overdose – toxic effects of methamphetamine, fentanyl, codeine and morphine. But circumstances surrounding her death were unclear. When local officers arrived to investigate her death, they found “the scene was compromised”, a report by the Milan police department – the local police department called to respond to Williams’ death – says, because Williams’ body had already been placed in a body bag and tagged.

And weeks later, despite lawyers’ requests to preserve evidence, security footage of Williams’ last hours alive had been deleted by CoreCivic’s camera system, according to emails from CoreCivic attorneys quoted in a wrongful death lawsuit.

“She never even got to start her sentence. It was a death sentence. Basically Cibola became her executioner,” Petrides said. “ I foolishly thought that because she was in what was supposed to be a facility where people were being paid to take care of her, that she was safe. And she was not.”

Cibola is supposed to be a secure facility, contracting with the Departments of Justice and Homeland Security, with a stated zero tolerance for contraband. Deaths are supposed to be an anomaly. But at Cibola, Williams’ death is one of many, the Guardian has found in an exclusive investigation.

Since 2018, at least 15 people detained at the Cibola facility have died, according to numerous documents including local police reports, 911 call records, New Mexico medical investigator reports, wrongful death lawsuits and a video from inside the facility. The deaths include at least 10 suicides, two overdoses, two deaths from prior health problems and one “undetermined” death, as stated in the hundreds of pages of documents gathered by the Guardian.

However, last fall, CoreCivic pitched the facility to the Department of Homeland Security as an ideal location to detain more immigrants, according to documents obtained by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU).

Around that time, coincidentally, the FBI launched an investigation into a network of gangs smuggling drugs and contraband into the facility, in September 2024. An FBI special agent described in an affidavit a “drug trafficking epidemic” at the prison and even alleged that some corrupt CoreCivic guards worked with the gangs to introduce contraband into the facility.

Although the FBI investigation has primarily focused on smuggling into the units holding USMS and local county detainees within Cibola, further reporting by the Guardian reveals that drug smuggling and consumption have been occurring in the Ice units, too.

The revelations come amid an increase in contracts for CoreCivic under the Trump administration, including for federal immigration facilities.

In response to a request for comment, CoreCivic, a publicly traded company based in Tennessee and operating across the US, sent a statement.

“At all our facilities, including the Cibola County Correctional Center (CCCC), the safety, health and well-being of the individuals entrusted to our care and our dedicated staff is our top priority. This commitment is shared by our government partners,” the company said.

The statement continued: “Our facilities have trained emergency response teams who work to ensure that any individual in distress receives appropriate medical care, and we are deeply saddened by and take very seriously the passing of any individual in our care. Any death is immediately reported to our government partners and investigated thoroughly and transparently.”

The Department of Homeland Security, which oversees Ice, has denied any drug smuggling is taking place inside the Ice units at Cibola, saying any such allegations are false.

But the prison is operating under a cloud of suspicion. By relying on hundreds of pages of federal and local law enforcement documents, along with court records, medical reports and interviews, the Guardian has uncovered shocking allegations of mismanagement, corrupt guards, drug smuggling and medical neglect. These allegations focus chiefly on the units not used for Ice detention, but additional reporting indicates that the Ice units are not immune from drug smuggling and associated violence.

CoreCivic did not respond to requests by the Guardian for comment for this investigative series specifically relating to allegations of drug smuggling involving areas where Ice detainees are held, although it acknowledged drug problems in the wider facility and confirmed it has been cooperating with the FBI’s investigation.

But in an interview, one man detained in one of the Ice units, whom the Guardian is not naming to protect his safety, said he had been a witness to drug smuggling, purchasing and consumption within his unit.

Meanwhile, multiple experts the Guardian spoke with considered the death toll at Cibola – 15 deaths in seven years, from 2018 to 2025 – to be alarmingly high, considering the facility’s capacity to hold only about 1,129 people.

Last year, the justice department’s inspector general released a report documenting federal Bureau of Prisons (BoP) institutions with high death rates. Although CoreCivic challenges any direct comparisons, if Cibola were a government-run, BoP facility, its death rate would land it among the worst performers.

“CoreCivic struggles to keep CCCC operating in a safe and efficient manner, confronting many of the same issues that face other correctional facilities nationwide,” an FBI affidavit relating to the agency’s investigation of drug smuggling at the prison reads. “The quantities of drugs seized are exceptionally large, given that they are located within a secure federal facility.”

The high number of detainee deaths at the facility that the Guardian has reviewed included only one, high-profile death of an Ice detainee, in 2018.

Advocates are shocked at the toll.

“ There have been a remarkable number of deaths for such a small facility,” said Laura Schauer Ives, a civil rights attorney representing Williams’ estate in an ongoing lawsuit in a New Mexico federal court against CoreCivic. “CoreCivic has done this work for decades, but they’ve failed and continue to fail their most basic duties – and those include keeping drugs out of the facility and keeping people in their custody alive.”

Williams’ wrongful death lawsuit was filed earlier this year, so there have been limited filings from CoreCivic attorneys in the case so far. In one filing, though, CoreCivic said that the company is “obligated to follow medical care instructions and directives issued by USMS”, including medical care directives concerning Williams. The company also said that its management of the facility was “monitored, inspected, and approved” by the US government, including the justice department, “who ensured that CoreCivic Defendants’ staffing pattern and qualifications conformed to requirements established” by the US government.

CoreCivic has denied wrongdoing in the civil cases it has faced. Meanwhile, the company said it could not provide the Guardian with specific comments related to Williams’ case or other deaths that have taken place at Cibola because of ongoing lawsuits and past settlements.

Tracking down statistics and details of deaths that have taken place at Cibola is challenging. According to an internal USMS policy document accessed by the Guardian through a Freedom of Information Act request, the federal law enforcement agency does not investigate deaths of people in its custody; it relies on local law enforcement agencies to carry out that work and only conducts a “preliminary review”. The USMS also does not publicly announce inmate deaths within its detention network. In contrast, Ice publishes a press release and launches an internal investigation into deaths of people in its custody.

To establish a total for the period in question, the Guardian accessed local police reports, medical investigator reports, and lawsuits to cross-check and document the number of deaths.

“CoreCivic is paid lots and lots of money to do this [detention work]. And unfortunately, CoreCivic appears to be operating with profit in mind and not the community interest,” Ives said. “ It’s in everybody’s interest that anybody in that facility is treated with basic decency. And it’s in everybody’s interest that people in that facility do not have access to [illicit] drugs. And it’s in everybody’s interest that people are not dying. And yet it persists, and they’re continuing to house people there to this day.”

Cibola became the subject of scrutiny in 2018 due to Roxsana Hernández’s death. Hernández was a transgender asylum seeker from Honduras who died after being held at Cibola while in Ice custody. CoreCivic’s response to her death investigation was eerily similar to Williams’ – in both cases, CoreCivic’s system had deleted video footage of their last hours alive. According to records obtained by the Guardian, Hernández has been the only Ice detainee who has died at Cibola – the other 14 who died there had been in the custody of the USMS or local officials.

The Guardian found that the suicides were overwhelmingly of people who hanged themselves in cells. Federal facilities have policies in place to prevent suicides and self-harm and, according to the Cibola contract, CoreCivic staff are required to regularly check on detainees suffering from mental illness, specifying that those who are deemed suicidal need to be “under constant observation”.

“I don’t understand why Congress hasn’t taken any action. I don’t understand why taxpayers put up with this,” said Parrish Collins, a civil rights attorney based in New Mexico who specializes in prison conditions and represents prison staff whistleblowers who sound the alarm about large government contracts with private prison operators like CoreCivic.

Collins is representing the estate of James Ramirez in a wrongful death lawsuit against CoreCivic and the local hospital that treated him, after the 28-year-old’s death in USMS custody at Cibola following an alleged delay in calling for an ambulance when he was injured from repeatedly collapsing in a medical observation cell. Company lawyers in a court filing have denied all liability and wrongdoing and speculated that Ramirez may have been “under the influence of drugs or alcohol” the day before his death. Because the lawsuit is still ongoing, CoreCivic said it could not comment on Ramirez’s specific case.

Meanwhile, in February of last year, two brothers were sharing a cell at Cibola when tragedy struck. One of the brothers, Dominic, was continually sleeping, facing withdrawal symptoms for his opioid addiction. And according to a local police report, his brother, Isaac, had been using crystal meth and “acting strange”.

According to the police report, at one point three other inmates arrived at the cell to offer Isaac drugs that had been smuggled into the facility. But they found Isaac dead by suicide, his brother asleep next to him. Dominic woke up to the traumatic chaos of guards and medical staff trying and failing to revive his brother, the local police report said.

The facility has faced allegations of mismanagement, understaffing and a lack of oversight. Multiple wrongful death lawsuits have been filed in the New Mexico federal court against CoreCivic, including for two other deaths by suicide, those of Justin Krantz and Zachary Asher. CoreCivic has denied allegations of wrongdoing.

Krantz and Asher, 36 and 31 years old, respectively, both took their own lives in their cells, according to lawsuits that claim that CoreCivic failed to properly monitor them despite signs they were suicidal. Court filings in both cases show that CoreCivic attorneys denied that the company and its employees’ practices were responsible for their deaths. Both cases were later settled.

Ramón Soto, a civil rights attorney in New Mexico, who represented Krantz’s estate and also worked on Asher’s case during their wrongful death lawsuits, said that due to alleged medical neglect and easy access to drugs, those entering Cibola with substance abuse issues or mental illness find their problems are exacerbated once inside the facility. “That’s when suicidal ideations skyrocket,” Soto said.

Williams’ and Ramirez’s wrongful death lawsuits continue to be litigated. The USMS did not respond to a detailed request for comment for this series.

“I think it’s irresponsible for the government to keep giving them money,” Soto said, adding that CoreCivic may see wrongful death lawsuits and any related settlements as a “cost of business”.

The company disagrees, calling such a characterization “deeply misguided and offensive”.

“Every death is a serious matter that demands thorough investigation, accountability and, most importantly, a commitment to prevention,” CoreCivic said in response to a request for comment. “The health and safety of every individual in our care is not optional – it’s a core responsibility. Our focus remains on doing everything possible to prevent these events from happening in the first place through training, oversight and continuous improvement in our standard of care.”

The trauma for family members endures. According to Petrides, Williams’ mother, she found out about her daughter’s death because another inmate at Cibola contacted a loved one after finding their number in Williams’ cell. It was not until six hours later that CoreCivic finally called Petrides to give her the news of her daughter’s death, without any further insight as to how she died. The USMS never contacted her.

“Had she been able to do her time and get out and be successful, she could have maybe helped people in her situation, because she did have a very kind heart,” Petrides said. “I want [CoreCivic] to understand that people are not for profit. They are important. And I do not want this to happen to anybody else’s daughter.”

-

Next week: part 3 of the Guardian investigation into the Cibola county correctional center

• In the US, you can call or text the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988, chat on 988lifeline.org, or text HOME to 741741 to connect with a crisis counselor. In the UK and Ireland, Samaritans can be contacted on freephone 116 123, or email jo@samaritans.org or jo@samaritans.ie. In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is 13 11 14. Other international helplines can be found at befrienders.org