There is a photo – or at least a “fabled” photo – that would tie up a lot of loose ends in the strange story of Winston Churchill’s platypuses.

Recent research has revived the tale of how the British prime minister asked Australia to send him a live monotreme at the height of the second world war. Sadly his namesake, Winston, died just two days before landing in England in 1943 in now disputed circumstances.

But Associate Prof Nancy Cushing, an environmental history specialist at the University of Newcastle, says Winston’s journey would never have happened without the knowledge gained from a second platypus, Splash, that was also sent to Churchill – albeit after it had died and been stuffed.

Cushing describes the connection between Churchill and the platypuses as “weirdly compelling”. Splash sat on Churchill’s desk while Operation Platypus – a series of reconnaissance missions in Borneo – was under way, academic research has found.

“I think one thing we would have loved to have found, and is fabled to exist, is a photograph of Splash on Churchill’s desk,” Cushing says. “There hasn’t been really any discussion of [Splash’s journey to London]. And that was such a breakthrough.

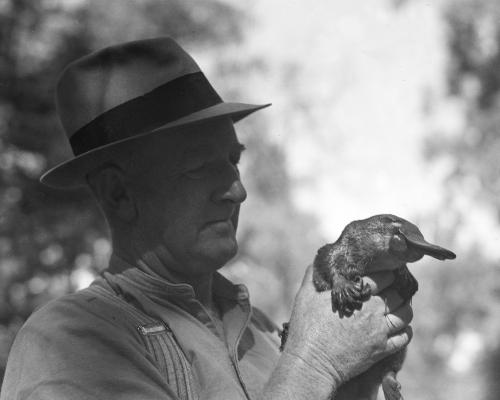

Before its death, Splash was the first of the sensitive, duck-billed, beaverish animals to be successfully kept in captivity by Healesville Sanctuary’s Robert Eadie.

“Without Splash there wouldn’t have been an attempt to send Winston. He defined how you look after a platypus in captivity.”

‘Magnificently idiotic’

Churchill famously kept a menagerie, which included kangaroos and black swans. In 1943, he asked Australia’s external affairs minister, Herbert “Doc” Evatt, if he could have not just one platypus, but half a dozen, a request described by the zoo owner and author Gerald Durrell as “magnificently idiotic”.

Monotremes, which include echidnas as well as platypuses, are distinct from other mammals because they lay eggs. With their duck-like bill, flat tail and partially webbed feet, they are so strange looking that many early European scientists studying specimens suspected they were a hoax.

Cushing and Kevin Markwell, from Southern Cross University, wrote in 2009 in their paper Platypus diplomacy: animals gifts in international relations that efforts to fulfil Churchill’s request were motivated by a desire to secure his “personal affection” towards an Australia “which felt abandoned by Britain during the war”.

“The feat of transferring the platypus would have brought acclaim to the Australians and viewing the platypus [at London zoo] would have reminded embattled Londoners of their Australian cousins who were also facing the grim realities of war while raising morale by providing an opportunity to see an exotic animal for the first time,” they wrote in the Journal of Australian Studies.

Officials charged with satisfying the British PM’s request approached Australia’s “father of conservation”, David Fleay, for help. Fleay wrote of his surprise in his 1980 book Paradoxical Platypus: hobnobbing with duckbills.

“Winston Churchill had found time suddenly in the middle of the war to attempt to bring to fruition what was, apparently, a long-cherished ambition … he had actually approached our prime minister for no less than six platypuses!” he wrote.

He described it as the “shock of a lifetime” and a “tremendous problem landed squarely in my lap”.

Fleay pushed back against the idea of sending six platypuses on the dangerous mission, but caught several and picked one to go. He named him Winston, built a “special travelling platypusary” for him (with burrows and a swimming tank) and trained a platypus keeper to look after him on the ship.

“I thought it was a really weird thing to do when you’re running a country, running a war,” Fleay’s son, Stephen, tells Guardian Australia from Portugal.

The platypus mission was secret at the time, but Stephen gradually learned about it and says his father supervised the whole thing.

“They’re very, very difficult to keep,” he says. “But he was completely, completely devoted to the animal.”

Splash the ‘tame platypus’

Fleay built his knowledge on the work of Eadie, his predecessor at Healesville Sanctuary. “We occupied his original cottage when my father became director in ‘37, ‘38,” Stephen says.

“He did a lot of pioneering work with the platypus, then my father took up his work.”

It was Eadie who had successfully kept Splash in captivity until its death in 1937. Cushing and Markwell, referring to Eadie’s own writings, wrote that the preserved remains of Splash were “carefully packed and secretly despatched to London”.

“When delivered to 10 Downing Street on 19 June 1943, accompanied by a leather-bound scientific description of the platypus and Eadie’s 1935 book The Life and Habits of the Platypus, with Sidelights on ‘Splash’ the Tame Platypus, Churchill was said to have been delighted and later to have displayed the platypus on his desk.”

The University of Cambridge’s Natalie Lawrence wrote in the BBC Wildlife Magazine that Splash, who had been a “minor celebrity” in Australia, was sent as an “interim gift” while plans were made to keep Winston alive on the long sea journey.

“[Splash] became almost entirely tame from his training by Robert Eadie, who had, as it happened, once saved Churchill’s life in the Boer war in South Africa,” Lawrence wrote.

Brisbane’s Courier Mail reported in 1949, in an article about Eadie’s death, that he had indeed been part of a team that helped Churchill escape from captivity (though other accounts have him escaping on his own).

Depth charges and heatstroke

Winston the platypus set sail on the MV Port Philip, but died just two days before he was due to reach land. The media at the time reported, presumably on advice of the authorities, that the Germans were to blame.

On 1 November 1945, Adelaide’s the News reported that Churchill, “in the midst of his war-time worries, wanted an Australian platypus”.

“And he would have got a specimen, a husky young male, but for German submarines,” the paper reported.

Depth charges dropped when the Port Philip encountered the submarines caused the platypus to die of shock, the paper said.

Fleay wrote that a heavy concussion would have killed the sensitive creatures.

“After all, a small animal equipped with a nerve-packed, super-sensitive bill, able to detect even the delicate movements of a mosquito wriggler on stream bottoms in the dark of night, cannot hope to cope with man-made enormities such as violent explosions,” he wrote.

But students from the University of Sydney studying Fleay’s collections in the Australian Museum Archives said in June that a shortage of worms to feed Winston, alongside heat stress, could have been factors as well as potential distress from the detonations.

The ship’s logbook shows air temperatures soared above 30C and water temperatures rose above 27C for about a week as the ship crossed equatorial waters. Platypuses cannot regulate their body temperatures in environments warmer than 25C, the students wrote.

“Heat stress alone would have been enough to kill Winston,” they wrote.

“However, it is important to note that food restrictions and the shock of a depth charge, in combination with heat stress, likely had an additional impact on Winston’e wellbeing and together contributed to his demise.”