Following emancipation, Jack Johnson had one major goal: to reunite his family. Johnson had been enslaved in North Carolina, Alabama, Louisiana and Mississippi, and had 10 children with JoAnna, his first wife, and another 10 with Hettie Brown, his second wife after enslavement.

Though Johnson managed to find nine of the 10 children he had with JoAnna, the family fruitlessly tried to locate the last child, Rufus. Johnson eventually learned that Rufus had been sold with two other enslaved people to a plantation in Texas. But to this day, Johnson’s descendants continue to search for Rufus’s living relatives.

From emancipation to reconstruction, Black families attempted to reconnect after the destruction wrought by slavery. Formerly enslaved people constantly looked for family members who, like Rufus, had been sold away. They placed advertisements in newspapers, asked strangers, searched faces and returned to the lands on which they had been enslaved in hopes of reuniting.

The tradition of Black family reunions was born out of this search, and continues throughout the US today with hundreds of thousands of families connecting, reconnecting and celebrating together annually, usually throughout the summer.

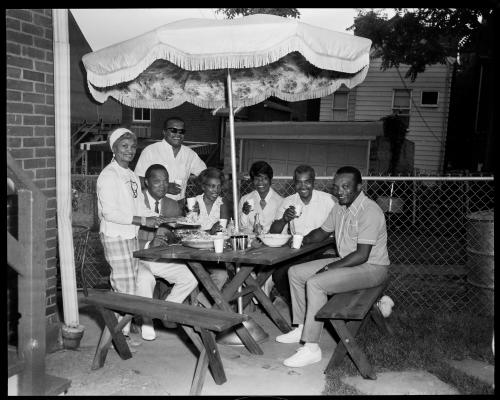

The festivities are a time where family members can meet for the first time, catch up over the time passed since they last saw each other and remember relatives who have passed away. They often include teaching and learning family ancestry and history, and cooking and sharing meals with traditional foods.

Nearly two centuries after Johnson began gathering his family, his descendants met in New Orleans, Louisiana, for a family reunion. Continuing Johnson’s legacy is central to the reunion’s theme. The family has a website, started by Elaine Perryman, dedicated to consolidating and spreading family history.

Ashanté Reese, an associate professor of African and African diaspora studies at the University of Texas at Austin, has been researching Black gatherings for the last two and a half years, attending multiple family reunions across the country.

“This is a thing that makes reunion so special, the tradition that it comes from,” said Reese. “Reading those advertisements, seeing that hope on paper, just made me even more committed to this tradition. These are people who were using the last little bit of money or the last bit of social capital they have. We have all this stuff at our fingertips to be able to stay connected. It feels important to me to honor the longing of people who were recently emancipated by being invested in this tradition.”

Christina McField was in charge of organizing the Johnson family reunion this year. Relatives who moved out of the region, such as cousins from Colorado, California, Ohio, Oregon, all journeyed south to unite.

“All of us are still coming together for this family reunion and we’re still finding out about more and more family members,” said McField, who is from Mississippi, where the family originated. “It seems to spread and get bigger every year.”

‘To the land where it all started’

The reunions Reese surveyed were in public spaces, and those that came together made the areas their own. “Black people gathering in large quantities in parks is a radical act when we think about how public space has been weaponized against Black people,” she said. “It never stopped being amazing to me that 200 or 300 folks would get together and take over a park for a day.”

One of the reasons that places have become important for family reunions is displacement and land loss. But for families that can return to their ancestral lands, doing so can be beautiful. This year, because the Johnson family was so close to Mississippi, after the reunion in nearby New Orleans, several people decided to drive “to the land where it all started”, McField said.

McField, an artist whose work is now on view at the Mississippi Museum of Art (MMA), said that her art was derived from the land and stories her mother told her about family members who lived there. She’s inspired by people like Isiah Jones, father-in-law of Mattie Hazeline Johnson Jones, who was the granddaughter of Jack Johnson. McField’s childhood home included heirlooms passed down through the generations, including a table from Jones that is also on view at the MMA.

Hiweda Jones, McField’s mother, said that she was just glad to be able to breathe in the air when she returned to Mississippi with her children who had never been before. She last visited the family’s land about 40 years ago, with her sister and Mattie Jones, who shared stories about her grandfather. He had 10 children born into slavery and managed to find all but one after emancipation. Meeting with Perryman, who McField and Jones said confirmed the family lore with a record, has been particularly moving for them.

“I don’t have the words to describe how I felt during that time, up on the porch around the house,” Jones said. “We were able to walk up in there and take pictures all through the trees. It was breathtaking.”

‘Each and every one of us has a story’

In 1926, the Quander family of Virginia and Washington DC held their first family reunion in Woodlawn, Virginia, near the Woodlawn plantation, where members of the family own land.

The Quander family is considered the oldest documented Black American family, with roots tracing back to the 1600s, before the US was a country. The Quanders of Maryland, the second main branch of the family today, began their own family reunion tradition in 1974.

Rohulamin Quander told the Guardian that he hopes these family reunions teach people from all families the importance of their ancestors. “Each and every one of us has a story,” said Quander. “Your story can tie you into an ancestor who worked very hard to make it possible for the future generations to have something. It is so important for African Americans to know and understand that the heroes and their sheroes are often right there in their family.”

Reuniting each year gives the Quander family an opportunity to internalize their history and ancestry. “We needed to stop, take a look, recollect, and share what the forebears did so that we understand that grandma’s hands may have been arthritic, may have been gnawed up, may have been very tired, she may have been stooped, but she [supported] the future. She did not necessarily live to see the success that her children or grandchildren or great-grandchildren reached. But we are standing on that bent-over back.”

Quander said that the first Quander reunion happened in 1925, after the family had three deaths in quick succession. They realized they should come together to celebrate, not only to mourn, and planned the event via letter. Forty-two people showed up. Vestiges of that family reunion continue today, such as the menu: “fried chicken and everything that goes with it”. They’ve come together every year since, except for a spell during the second world war and then again in 2020 at the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, when they met via Zoom instead. This year, for the 100th reunion, the Quanders had a three-day event, which included a program at Howard University, a picnic at Mount Vernon and a sit-down dinner.

‘It doesn’t matter if it’s five or 50 people’

Though regular gatherings among Black families aren’t rare or unique, they aren’t usually considered a family reunion if they lack one of the most lasting identifiers: a reunion T-shirt. “Having that artistic, creative, sartorial choice as a part of the reunion is really important, too,” Reese said. “The shirts are just about uniformity. They tell you things about the family. They tell you about the style and the preferences for that particular year.”

For Sade Meeks, who told the Guardian that though her family meets annually for holidays, it wasn’t until this year, when her cousin designed shirts for the gathering, that she began to think of it as a family reunion. “It doesn’t matter if it’s five or 50 people. We have this perception like if it’s not 100 people in T-shirts, it’s not a reunion,” she said. “I think we have to shift our perspective and understand like it’s not about the numbers, it is literally about just being together.”

Bringing family from California and Chicago together in Mississippi was something that was important to all the generations in the Meeks family. It allowed for intergenerational moments, like when Meeks’s mom joined in the kitchen to teach her cousin how to cook whiting.

Meeks remembered being annoyed with her late uncle, who would always take photos at family gatherings, when she was growing up. But this year, she was the one to take the photos. “Somebody has to do it, because we’re going to look back and this may be all we have,” she said. “Sometimes we don’t realize how important photos are when it comes to memories and things like that.”

While attending various family reunions, Reese said that she would ask the young people, many of whom were in their 20s and 30s, around her what they thought about the gathering.

“One of the things that they said was: ‘Nobody ever asks us our opinion. They want us to come, they want us to help, but they don’t ask us about the planning,’” she said. People she’d talk to would have big ideas for how they’d run things or just small tweaks or additions they’d make to the schedule, but they were never included when it came to organizing the reunion.

McField, who is in her 30s, didn’t have to go at planning the Johnson family reunion alone; Perryman, who’s a more senior member of the family, helped act as a guide and provided support. But it was also important to McField that she take on the responsibility – and now she can act as proof to other younger people that it’s something they can do as well.

“We need more people to see the value in wanting to keep this going, the value in learning about our family’s history,” McField said. “The next generation from us has already started. If we don’t take it on, there’s more people who are passing away. If it goes flat, it disappears again. I want to build off of what we just did, the camaraderie and the excitement from it.”