It was supposed to be a special occasion: an extended family get-together for Sunday lunch at a country pub. The setting was promising: a traditional establishment recently redecorated; outside terrace by the river; plenty of customers. The menu was also promising: a giant sheet of paper like a medieval charter, with glowing descriptions of how they aged their beef and sourced their produce locally.

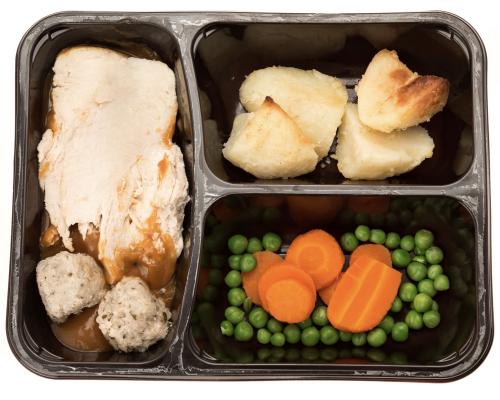

The food, though, was awful. The starters were assorted deep-fried pellets of unidentifiable organic matter; the meat was cold and colourless, the gravy watery, the roast potatoes soggy and the yorkshire pudding chewy as a dishcloth. It was very difficult to believe all of this had been freshly prepared in the kitchen that day. It felt more like reheated leftovers – for £30 a head.

You may, like me, have had this experience – and the lower-budget equivalent, the pub menu that consists of 700 variations of pie or burger, all of which arrive at the table via the freezer and the microwave, molten hot and almost glowing. With chips.

How did pub food get so grim? We like to think the bad old days of British cuisine, the days when it was a national embarrassment, are far behind us, that the 1990s and 2000s ushered in a wave of quality gastropubs and that the shires are bursting with talented chefs cooking local produce from scratch. In some cases, that is true, but more broadly – in my view, at least – pub food in the UK is on the decline.

“You’re definitely not alone,” says Katie Mather, a drinks writer and pub culture blogger. “There is evidence to support your hypothesis.”

Ray Bailey, one half of the bloggers Boak & Bailey and a co-author of 20th Century Pub, also agrees. “Pub food has quietly been on the decline for a few years now, both in terms of quality and availability. There was a golden period during which you could rely on being able to get a solid meal for a reasonable price, but now many pubs have closed their kitchens or outsourced food to fast food popups.”

Pubs have never had it so hard, you could argue. They face significant and often inexorably increasing costs: rent; staffing (partly as a result of the recent national insurance contribution increases); energy (to heat and chill food and people); alcohol (duty on a bottle of 14.5% red wine has risen by nearly £1 in the past two years); and food (one chef tells me beef has gone up 50% in the past eight months). This comes on top of Covid recovery and the cost of living crisis. According to the British Beer and Pub Association, 15,000 pubs have closed in the past 25 years. There are still roughly 45,000 left, but the UK is losing about six pubs a week.

“Pub food used to be the moneymaker, but with the rising price of literally everything, it really isn’t as cheap to do that any more,” says Mather. “For a long time, business owners have been able to hide the effects from customers to a certain degree; they’ve been able to cut corners in kind of invisible ways. But it’s become so difficult to deal with.”

Pubs have had it hard for a long time, says Brian Hannon, a co-founder of the London-based restaurant group Super 8, which includes Brat, Kiln and Smoking Goat. Previously, he worked for 18 years in the pub sector. The shake-up began with the beer orders in 1989. In an attempt to improve competition, the government limited the number of tied pubs a brewery could own to 2,000. At the time, 75% of UK pubs were controlled by six breweries (Bass, for example, had to sell nearly 5,000 of its 7,000 pubs) and 95% of their revenue came from drinks. This change created conditions for new pub chains and independents to flourish. By the time the beer orders were revoked, in 2003, the industry had been transformed.

Habits were changing, too. By the 2000s, we had what Hannon calls the three Fs: “Food, females and fenestration.” Pubs opened up literally and socially, while food revenues made up for declining drinks sales. It was the era of new chains, such as All Bar One, and the original gastropubs, such as the Eagle in Clerkenwell, London. Pub food became a route to culinary acclaim and celebrity. In 2001, the Stagg Inn in Herefordshire became the first pub to receive a Michelin star. The Hand and Flowers, Tom Kerridge’s pub in Marlow, Buckinghamshire, has two stars.

This era didn’t last long, though. “I refuse to use the word gastropub, because I don’t think it means anything any more,” says Oisín Rogers, the head chef at the Devonshire, one of London’s hottest pubs. “Gastropubs in the 90s and the 2000s were always chef or mom-and-pop operations where you’d have a single freeholder or leaseholder who was in the kitchen all the time, cooking from scratch, making really delicious things in a place they were really proud of. And that was copied by the [pub chains]. They’d say: ‘Look, this is a gastropub. It’s the same colour and the menu looks a bit similar,’ but actually you’re getting a far inferior product.” The Good Food Guide stopped using the term “gastropub” in 2011. These days, you are more likely to see the word in supermarkets: Marks & Spencer has a “Gastropub” range of ready meals created by Kerridge.

Hannon breaks down today’s pub food landscape into three brackets. At one end are those putting a premium on quality food and targeting customers willing to pay for it. At the other end are the big chain pubs, operating on the basis of low cost and high margins. “The lower the price, the more likely it’s been bought in and not been cooked by a chef,” Hannon says. However, he adds: “The chains will apply their skill set and their muscle to actually get not-bad food produced well.”

In the perilous middle ground, smaller chains and independent pubs try to present a gastropub-looking menu for minimum outlay and maximum profit, which, in this climate, necessitates compromises – and may well explain my unsatisfactory Sunday roast. (On closer inspection, the pub in question turned out to be part of a group, offering very similar menus across several sites, which suggests some degree of centralisation.)

“What often happens is the guy who’s running the pub has a spreadsheet that’s been sent down saying: ‘This is where you get your beef, this is where you get your yorkshire pudding, here’s the instructions on how to do it,’” says Rogers. “And they’ve followed the instructions, maybe not completely correctly, and ended up with an inferior product on the plate.”

Hannon says: “The people in the middle are making no money out of producing food because, number one, the cost of employing a chef is really high and, number two, it’s hard to actually get the staff, especially given that pubs are often out in the countryside. And then the economics of running those have been really challenged. So what they’re now doing is de-skilling their food.”

A pub menu will never say: “We don’t actually make this food ourselves.” But more and more pubs are quietly outsourcing some or all of their cooking. “We’ve heard stories of pub kitchens serving microwavable supermarket ready meals because they’re cheap, last for ever in the freezer and have incredibly high mark-up,” says Bailey. Even big names have been caught out. In 2009, Gordon Ramsay was found to have been serving food prepared at a central kitchen in three of his London gastropubs, presenting it as “freshly made”, at considerably inflated prices.

One indicator of this trend is the growth of external catering firms. Visit the website of Brakes, the market leader, and you will find more than 9,000 products: everything from fresh, raw ingredients to frozen pub grub – 20 formed cod fillets in batter for £1.69 each, yorkshire puddings for 35p each. They do 66 kinds of chip, says Paul Hulyer, Brakes’ head of hospitality customer marketing. He doesn’t provide exact figures on how their pub business is doing, but he says: “We’ve sustained very good, healthy volumes in the sector.”

Having worked for pub chains himself, Hulyer knows how the pressures have grown. “One of the things I’ve noticed is more pubs want to try to do some cooking,” he says. “When I worked in kitchens, everything was cooked from scratch, you had 12 people in the kitchen, whereas now, with all the increasing costs, you’ve got to do similar with four or five people. How do you do that? Well, you take some of the prep out. That’s what we help to do.”

For example, Brakes sells a whole beef brisket, Hulyer explains. “We’ve done the seven-, eight-hour cook so you’ve not had to. And [the pub kitchen] would take it, defrost it and portion it. And then they would say: ‘Right, I’m going to flavour this with …’ and they would personalise it.” If they don’t want to do even that, Brakes also offers a range of sauces.

Brakes is scrupulous about food standards and responsible sourcing, of course, but it has little control over what goes on in the kitchens it supplies (assuming anything is going on beyond setting a timer on a microwave) or how their products appear on menus. The language can often be wilfully obscure, with terms such as “homemade” and “freshly prepared” covering a multitude of sins, says Rogers. “Some of the big chains will say they do aged beef, for example, which doesn’t mean dry aged; it just means it’s been kept in a vacuum bag.” There are also dodgy supply chains, he says, such as what has been called “long-range chicken”, “where you buy chicken that was bred in Vietnam, packed in Singapore, injected with fillers in the Netherlands and then arrived frozen to a cash-and-carry in the UK”.

Everyone seems to have horror stories. “When I worked as a waiter in a chain pub in the 1990s, the ‘homemade’ steak and kidney pie was assembled from a sachet of brown goop emptied into a dish with an oval of pre-made pastry popped on top,” says Bailey.

The quality end of the pub food spectrum comes with its own challenges. While pub chains may operate on a profit margin of 70%, serving fresh, quality food is far less profitable, which inevitably means higher prices for customers. Mains at the Devonshire’s upstairs restaurant are £20 to £40, not counting side dishes, although they do cheaper bar snacks downstairs. Sunday lunch at the Hand and Flowers will set you back £175.

When that is the case, Mather asks, can we still call these places pubs? “I would argue that they focus so much on food that now they are just restaurants.” She defines a pub as “a place that I would feel comfortable drinking in without having a meal”. Those places do exist, she says, citing her local in Lancashire. “They do fantastic food, but I could sit in there with pints, just reading a book. I don’t feel as if I’m in the way, or taking up a table that someone else might eat at, whereas there are pubs that have gone completely the other way.” It’s almost as if “gastro” and “pub” are going their separate ways.

So how can you avoid disappointment with your pub meal? What are the warning signs?

“Because I’m in the industry, I always look at the tills,” says Rogers. “If the tills are the corporate type, where it’s the same system that’s run all over the country, then I’m always suspicious.”

Hannon says: “Look at the menu: size, focus, how it is actually presented. No laminated menus, no menus that try to be Chinese, Indian and Sunday roast. Talk to the staff about where the produce is from, how long the chef has been there.”

Rogers continues: “I think one way to spot a really good, decent pub menu is that it’s short. If you’ve got 35 main courses and 20 starters, you can be certain that most of that is in the freezer.” Look for closer to six starters, mains and desserts.

“If I go to a chain pub somewhere that I’ve not been to before and I look at the menu and it’s like ‘lasagne’, then you just know that that’s frozen and microwaved,” says Mather. “The fish and chips – that’s going to be frozen as well. Unless there’s a good specials menu, or it’s got really good local reviews, I would eat somewhere else.”

There may be other solutions. In 2014, France launched a fait maison (homemade) scheme, whereby restaurants that genuinely made their food in-house could display a special logo. The scheme never caught on, but there are plans to revive it and make it mandatory. At the same time, especially in UK cities, there has been a resurgence of what might be called “drinking pubs”, where the emphasis is on the beer or wine, rather than the food: microbreweries, tap rooms and the like.

There is also a growing appetite for locally owned pubs, says Mather, who just visited one in the Lake District. “Their food was fantastic and their entire staff seemed to care a lot about the food and drink that they’re serving.” Pubs were once the heart of the community and some places are successfully keeping them that way, not just with food and drink, but as gathering spaces for all manner of functions: artistic performances, family events, markets, workshops. The best boozers have always moved with the times, but also respected their hungry, cash-strapped customers – who can tolerate only so many soggy roast potatoes.