Warning: This article contains historical records that use racist and offensive language, and descriptions of events that will be distressing to some readers. It also contains references to Indigenous Australians who have died

In a bustling Newcastle suburb there is a large park where families gather under giant fig trees. Few know it is named after a man who killed Aboriginal people.

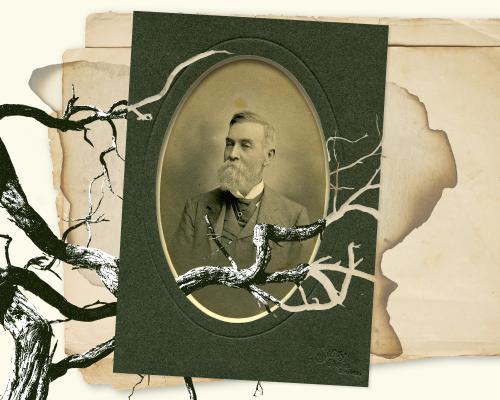

Gregson park was given to the local council in 1889 by Jesse Gregson, then the head of one of the nation’s most important enterprises, the Australian Agricultural Company.

AACo, today worth about $830m, is still Australia’s largest beef producer, with stations covering almost 1% of the nation’s land mass. Its majority shareholder is the UK billionaire Joe Lewis, whose family own Tottenham Hotspur, followed by the Australian mining magnate Andrew Forrest and his ex-wife, Nicola Forrest.

An investigation as part of Guardian Australia’s the Descendants series has revealed the company’s historical links with the dispossession, shooting and poisoning of Aboriginal people – through the exploits of Gregson before he joined the company, and others who helped establish its farming operations in the 19th century.

The discoveries raise complex questions about how longstanding Australian companies can reckon with past harms.

Before Gregson joined AACo in the 1870s, he managed a sheep station in central Queensland where he perpetrated a series of massacres that unleashed a bloody war.

Gregson arrived at Rainworth station, 300km inland from Rockhampton, in June 1861.

Queensland had become a self-governing colony two years earlier and the frontier was moving north, assisted by the notorious native police – contingents of Aboriginal troopers led by white officers tasked with protecting the livelihoods of settlers and punishing Aboriginal resistance.

As Gregson and his workers approached the station, they were greeted by Aboriginal people.

“We had been met by blacks who made overtures of peace by attaching white feathers to our horses’ bridles or anywhere they could stick them,” the pastoralist wrote in his memoirs. “As soon as the drays reached the camp I gave the blacks to understand that they must keep clear which they did good humouredly enough.”

The next month he and the native police went looking for some missing sheep, finding them on the side of a ridge with a Gayiri tribe.

They opened fire. Gregson describes the encounter as a “brush” but native police records show at least four Gayiri people were shot.

Months later, on the property next to Gregson’s, the Gayiri responded by killing 19 men, women and children – including the Victorian sheep farmer Horatio Wills, the father of Australian rules football co-founder Tom Wills. It was Queensland’s largest massacre of white settlers by Aboriginal people.

Gregson assembled a group of settlers to track those he believed to be responsible. Finding them within days, they shot the sleeping tribe, killing at least 30.

More reprisals would follow, led by native police and vigilantes, wiping out about 300 Aboriginal people.

There are various theories about what provoked the Wills massacre but the commonly held view among historians, Indigenous knowledge holders and Wills’ descendants is that the encounter with Gregson and the native police was a tipping point. It is believed that the Gayiri thought Horatio Wills was Gregson’s brother, and therefore an appropriate target for retribution.

About a decade later Gregson moved to Newcastle in New South Wales to take up the position of superintendent of AACo. He remains the company’s longest-serving superintendent, holding the position for 30 years and wrote one of the first histories of the company.

Darryl Black, a Bidjara and Ghungalu man from central Queensland who learnt of the massacres from his father, said Gregson “wasn’t a very good person at all”. He described Gregson’s appointment to the prestigious company as his “reward” for opening up the region to farming and grazing.

‘A place to be shunned’

Founded in 1824, AACo is the oldest continuously operating company in Australia. It was established by an act of British parliament when a handful of UK politicians, banking directors and business leaders were granted 1m acres of land around Port Stephens to raise sheep for fleece to be sold on the London market.

The Worimi historian John Maynard wrote that the company’s arrival on his ancestors’ country at a time when his people were being ravaged by violence and disease was both a lifeline and “another means of enforced organised brutality”.

The company employed Aboriginal people as stockmen, sailors, constables and domestic workers. When AACo experienced convict labour shortages, the company’s records show that Aboriginal workers helped fill the gap and were an essential part of its success.

Historical reports link the company to at least two shooting attacks on Aboriginal people near Newcastle in the Hunter Valley region, in 1830 and 1835, in retaliation for the spearing of shepherds and livestock.

In the later encounter, according to a 1922 newspaper article, soldiers retained by AACo joined local vigilantes in tracking an Aboriginal group who had speared five shepherds. The soldiers, fearing ambush, stopped before the rest of the group fired on the sleeping camp at a cliff’s edge – but according to the report later re-engaged to hunt down survivors.

“Maddened with fear under the gunfire they broke hither and thither in vain attempts to escape,” the article says of the clifftop encounter. “Panic stricken they turned to the cliff edge and sprang into space.”

About the same time, the same article claims that a group of convicts employed on an AACo station poisoned a group of Aboriginal people in retaliation for raids on cattle, by giving them damper laced with arsenic. It says they “lay down and died all around”. The modern-day suburb of Belbora (from the Worimi Baal Bora) is said to be named after the tragedy, meaning “a place to be shunned”.

AACo eventually sold its NSW properties and moved into cattle production. Today it holds 7m hectares across the Northern Territory and Queensland, including two properties within an hour of Gregson’s former station.

An AACo spokesperson told Guardian Australia: “We won’t and can’t comment on historical matters, especially given we don’t have access to records from the time.”

Most of the company’s records, dating back to 1824, are held at the Australian National University.

Last year, to mark its 200th anniversary, the company held an exhibition showcasing its history through archival photos, maps, drawings and papers held at the university.

The exhibition’s section on Aboriginal history said the Worimi people had been largely displaced by cedar getters (convicts who harvested timber) before AACo was established, but said the company “would also have displaced some of the local Worimi”.

James Fitzgerald, a legal consultant for the Australasian Centre for Corporate Responsibility, said companies had an obligation to confront the “evils of the past”.

“Just creeping along as though nothing happened is moral cowardice, particularly when it’s an enterprise that’s making money off dispossession,” he said.

“The more a company’s wealth is built on that sort of dispossession, I would have thought, the greater its obligation to take account of that as a decent corporate citizen in 2025.”

Fitzgerald said there were comparable cases where mining companies had made reparations through apologies, working with traditional owners to improve cultural heritage management, setting Indigenous employment targets or negotiating financial compensation.

The AACo spokesperson said the company had built “trusted relationships” with many traditional custodians across the properties managed. “We recognise their culture and deep connection to Country and work with them to ensure we engage respectfully,” they said.

Joe Lewis, through a spokesperson, declined to comment to Guardian Australia. Andrew and Nicola Forrest did not respond to questions.

Fitzgerald said the 1992 Mabo verdict, which recognised Indigenous peoples’ rights to their land, raised complex questions for Australian companies that had built their wealth on land taken from and cleared of Aboriginal people.

“If you keep pulling at the thread long enough, it implicates the entire basis of our sovereign state economy,” he said. “We are all the beneficiaries of these actions in one way or another, whether as real property owners, shareholders or super fund members.”

-

Indigenous Australians can call 13YARN on 13 92 76 for information and crisis support; or call Lifeline on 13 11 14, Mensline on 1300 789 978 or Beyond Blue on 1300 22 4636

-

Lorena Allam is a professor at the Jumbunna Institute for Indigenous research at the University of Technology Sydney