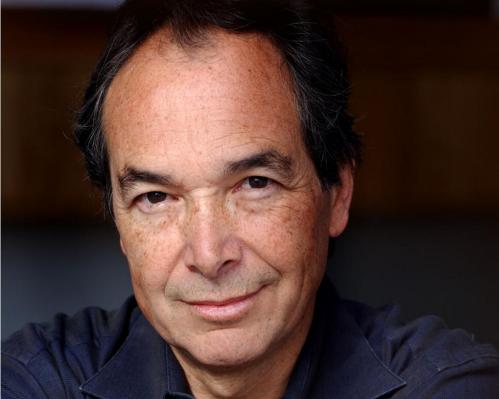

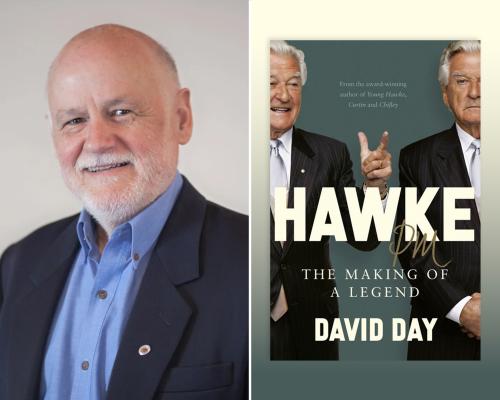

The second instalment of David Day’s biography of Bob Hawke, which chronicles the public and private lives of Labor’s longest-serving prime minister, is as masterful, gritty and in many ways as disturbing as the first.

The first, Young Hawke: The Making of a Larrikin, traced his life from birth through his unconventional upbringing, student days in Australia and Oxford, and his rise as a unionist amid eventual national expectation he’d one day become prime minister.

A portrait emerged of an unlikeable and perhaps pathological narcissist, a vicious drunk who apparently loved many women, including his long-suffering wife Hazel, while he was borderline predatory with others. The parallel story traced his rise as a worker’s hero and a friend to bosses, a peacemaker and king of consensus who made remarkable gains for ordinary Australians.

For a long time Hawke carried with him through public life a broad assumption he’d become PM. For Hawke, personally, it was fated. But he and his most assiduous supporters knew that even as Australia’s most celebrated “larrikin” (a catch-all, that, for blackout pisshead, lousy dad, worse husband and occasional sleaze) he would have to mend his wicked ways. At least for public consumption.

Hawke was self-aware enough to understand this as he entered parliament and immediately set about building his profile as a team-playing caucus member – all the while enjoying stratospheric political popularity and stalking Labor leader, Bill Hayden.

The Hawke marriage was pretty much over, except in name, when he entered parliament in 1980. He was still drinking heavily and found his lower-profile life on the backbench challenging. But to the amazement of many peers, he quit the booze and began to lead a more discreet personal life in his quest for prime ministership – a job he retained for a Labor record of almost nine years.

Quitting drink was not easy for one whose public wheels had been oiled by grog for more than three decades. But it was as critical to his ascent as a strategy to publicly air some of the worst aspects of his past through Blanche d’Alpuget’s 1982 biography, Robert J Hawke. Both decisions helped him become electorally presentable. (D’Alpuget, of course, became Hawke’s second wife after his political departure when Paul Keating rose, just as inevitably, and knocked him off as PM in December 1991.)

This public inoculation was a high-risk strategy that seems to have worked. As Day writes: “The fact that the biography was written by an excellent writer who also happened to be his lover, and that it was vetted by him and Hazel, would have given him some confidence about its likely reception. Moreover, as a narcissist, he expected to be forgiven and embraced whatever he did.’’

Those who’ve worked anywhere near politics understand its terrible toll on families; the effect on Hawke’s was devastating. There is a poignancy to how Day writes about the familial collateral on Hazel and their three children, Sue, Rosslyn and Stephen.

When Hawke was mustering support against Hayden he needed Victorian power broker Bill Landeryou’s backing. His daughter Rosslyn, then 21, had been working for Landeryou – a favour from the power broker “in the hope of distancing her from the Sydney drug culture’’ she’d become immersed in.

When Rosslyn alleged to her father that Landeryou had raped her, Day recounts how Hawke urged her not to go to the police so as to avoid controversy while he sought the Labor leadership.

“In convincing his daughter not to complain to the police, Hawke would have doubtless consoled himself that he was also protecting her, since any prosecution would have seen her … heroin use become the stuff of lurid headlines at a time when rapists were rarely convicted,” Day writes.

The Hawke marriage continued as a partnership throughout his prime ministership during which he oversaw (with Keating’s critical support as treasurer and as his sharpest parliamentary advocate) unprecedented social and economic reforms, not least the prices and incomes accord, the introduction of universal healthcare, compulsory superannuation and floating of the Australian dollar.

Lagging badly in the polls in late 1990 and his government adrift with Keating now on the backbench after his failed first leadership challenge, Liberal leader John Hewson released his Fightback manifesto with its centrepiece goods and services tax. Whereas Keating would have demolished Fightback, publicly and in parliament, a “transfixed’’ Hawke was a “rabbit in the headlights”. This was, Day concludes, Hawke’s undoing.

Those of us who grew up watching Hawke ascend, who voted for him in 1983 and benefited from his progressive new Australia won’t regret it when they read this book. But they will understand a lot more about the man’s fabric.

-

Hawke PM: The Making of a Legend by David Day is out now (HarperCollins Australia, $49.99)