Inflation has come down from the stratospheric peaks of December 2022, dropping to 2.1% in the year to June and towards the bottom of the Reserve Bank’s 2-3% target range.

That’s the good news: things generally aren’t getting more expensive at the same breakneck pace that they were a couple of years ago.

Then there’s the bad news: the biggest inflationary shock in a generation has left Australia a much more expensive place than it was before the pandemic.

And it could take years for households to catch up.

The headline inflation measure we use is the percentage change in the price of a basket of goods and services, and when it’s positive that means the price of things is still increasing.

So even though inflation is now “back to normal”, prices have generally remained at higher levels than usual and for the most part are likely to stay that way.

We’re very unlikely to see prices go down across the board (this would be deflation and would mean that something quite bad is happening to the economy).

Sign up: AU Breaking News email

So if prices are much higher and are still rising, the question is: when will the cost-of-living crisis be over?

Enter wage growth.

For the higher prices to feel “normal” again, we need enough growth in people’s wages (and other forms of income) to compensate for all the inflation that occurred over the last couple of years.

Economists refer to this concept as “purchasing power”, or how much your dollar can buy.

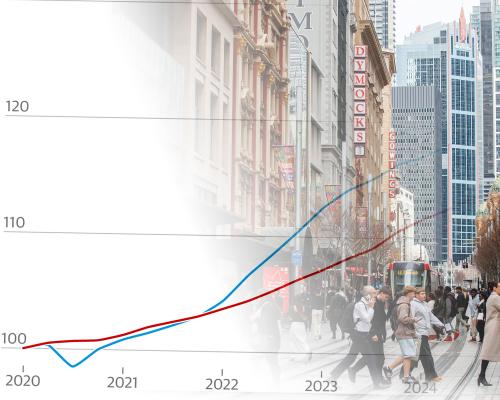

One way to figure out how long this might take is to compare the cumulative increase in inflation (the change in the consumer price index, or CPI) since 2020 with the cumulative increase in the wage price index (WPI), and then make some assumptions about how much they might increase in the future.

Once cumulative wage growth overtakes the overall increase in consumer prices, then we’re finally back to living costs feeling like they did in 2020.

So how long will this be? Well, if inflation averages 2.5% per year from now on (the midpoint of the Reserve Bank’s 2-3% target range), and wage growth averages 3.5%, things won’t feel normal for at least another three years:

You can change the assumptions in the chart for higher or lower values and see what you get, though the time series from the present onwards is capped at 10 years.

(Another way of doing this is to combine the two indices to get “real wages”.)

However, the wage price and consumer price indices are just one narrow way to look at this issue.

WPI measures hourly wage and salary rates, so it doesn’t capture other aspects of a worker’s compensation like additional hours worked or promotions, according to Trent Wiltshire, an economist at the Grattan Institute.

Wiltshire says there are other measures, such as average weekly earnings, that can measure people’s income in a more comprehensive way.

“There are broader measures [than WPI] that capture the fact that people can work more hours in a stronger labour market, and in a stronger labour market people are more likely to get promoted if they’re switching jobs, or if firms are keen to keep workers,” he said.

“One of the great things we’ve seen since Covid is that unemployment has remained low, but it has taken a while for that to flow through to higher wages.”

Weekly earnings have increased faster than WPI over the past two years, meaning that if we index them to compare with CPI in a similar way, then they have just caught up.

And on the inflation side, the Australian Bureau of Statistics also publishes a better measure of cost of living than CPI, though it is less known. The selected living cost index series shows how price changes affect the living costs of different types of households.

The most notable difference is that the employee living cost index includes the impact of the change in mortgage interest rates, whereas CPI doesn’t. So it has grown even more strongly than CPI, due to rate rises in 2022 and 2023.

Here, we can compare the higher living cost index to see how things have changed since 2020 and how much earnings would have to grow to catch up:

Even using these broader and more realistic measures of income and living costs, we end up with the same story: cost of living could remain a major issue for Australians until early 2029.

Of course, a lot can happen over the coming years to change this grim outlook.

The treasurer, Jim Chalmers, has switched his focus from getting inflation back under control to ways to boost growth – his economic reform roundtable later this month will hopefully create some good ideas to this end.

But reforms tend to take a while to bear fruit. In the meantime, Australians are likely to continue to feel under pressure.

Notes

CPI and WPI were indexed to 100 in December 2019.

Weekly earnings are the seasonally adjusted “all employees average weekly total earnings” from the ABS, indexed to 100 in November 2019, then with “missing” quarterly values between the biannual figures interpolated linearly.

The living cost index is the employee living cost index from the ABS Selected Living Cost Indexes publication, indexed to 100 in December 2019.