It is 1.30am in the New South Wales town of Moree, and a 16-year-old passenger in a stolen Audi is using his phone to film the speedometer as the needle climbs towards 150km/h.

He shares the video with his friends on the social media app Snapchat, a court later hearing he thought it was a “cool thing to do”.

But in NSW – and increasingly across the country – such posts are illegal.

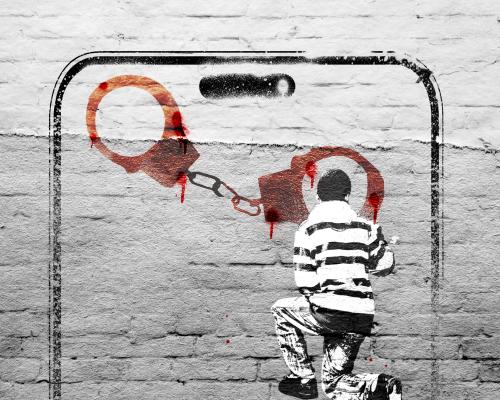

This week, the Victorian and Western Australian parliaments became the latest to consider so-called “post and boast” laws, as almost every jurisdiction in the country makes it illegal for offenders to publish footage of their crimes on social media.

The laws passed in Victoria on Thursday, but will be considered by a parliamentary committee in WA before being put to a vote there.

The introduction of such reforms has come despite legal and human rights groups repeatedly arguing the laws are both harmful and pointless, as they create a further mechanism for locking up young people under the false pretence of addressing a problem already handled under existing law.

“We’re seeing a troubling race to the bottom across the country, with governments in multiple states competing to be the toughest on children in the justice system,” Dr Mindy Sotiri, executive director of the Justice Reform Initiative, says.

“‘Post and boast’ laws sound catchy and might work for political point-scoring in the short term but are ultimately just a headline-grabbing distraction. The reality is these laws will be completely ineffective.

“They won’t deter offending, they won’t shift the way children and young people are using social media, and they won’t address the drivers of crime. What these laws will do is drive more and more children deeper into a failing justice system.”

The Moree case referred to a youth offender known by the pseudonym Nadj. His case is one of few publicly available court decisions about someone charged under the laws.

Sign up: AU Breaking News email

The children’s magistrate in his case found that there was no evidence Nadj was motivated by “posting and boasting” when the car was stolen, that there was no information about how many people saw the Snapchat post, and that there was nothing in the post that would give others information about how to steal cars.

“The public policy rationale for this offence is that boasting has the capacity to encourage others to engage in criminal behaviour,” children’s magistrate Paul Hayes found in his decision from March this year.

“It might send the message to impressionable young people that criminal acts are socially acceptable. It may make others think it is desirable to commit crimes. It might influence people to commit offences to circulate on social media. It may also provide people with information or ideas about how to commit criminal offences. Posting and boasting glorifies crime.

“Nadj says that the posting is a ‘cool thing to do’ but isolates this to his peer group … in this case the seriousness is the dissemination – not so much the effect.”

Nadj could have been penalised with a maximum two years’ imprisonment under the laws, but Hayes found the post would not greatly contribute to his aggregate sentence for other offences.

A month earlier, Hayes dismissed similar charges involving a boy known by the pseudonym Harry, who was 13 when he was also allegedly involved in stealing a car and “disseminated material” about this theft, leading to a “post and boast” offence.

The first state to implement the laws was Queensland, when the then Labor government, facing intense criticism over its response to crime, passed them in early 2023.

The Minns government in NSW followed suit, passing similar laws in March 2024, and the Northern Territory government also implemented post-and-boast offences with two-year maximums in October last year after sweeping to power on a tough-on-crime mandate.

South Australian laws were next, after they were introduced by an independent upper house MP, Frank Pangallo, who wanted a presumption against bail for youth offenders who posted and boasted about their crimes. That measure did not pass parliament, but another version of the laws – which also had two-year maximum penalties – did.

“Criminals can seek to gain notoriety by posting and boasting which could potentially incite or encourage others, and further embolden their own illegal acts,” the attorney general, Kyam Maher, said in a statement in May.

“This legislation is an important step forward in protecting the community from offenders who seek to glorify illicit activities.”

The rhetoric used by Maher is common when governments trumpet these changes in media releases. There are repeated references to “crimfluencer”, a pun on social media influencers, and wordplay such as “no likes for lawbreakers”.

The Tasmanian government promised it would introduce similar laws last year, while the ACT government has no plans to introduce them. Peter Dutton even promised federal post-and-boast laws had the Coalition won the May election.

The laws generally only apply to certain offences, and in some cases include carve-outs to ensure that media coverage or awareness campaigns are not endangered.

Sonya Kilkenny, the Victorian attorney general, said in her second reading speech that the bill now meant a person who posted online about a home invasion faced a maximum penalty of 27 years in prison: 25 for the home invasion, and two for the post.

“One of the challenges confronting our community today is the rise of ‘posting and boasting’ about criminal offending,” Kilkenny told parliament in June.

“The performative nature of these offences introduces a new layer of harm: it glorifies criminal behaviour, encourages others to emulate it, exacerbates community concerns and fear, and erodes public confidence in the justice system. It may also publicly identify and retraumatise victims.”

‘No long-term benefit to community safety’

Performative is exactly how critics of the laws describe the governments who are passing them.

Judges and magistrates could already consider the fact a person posted about their crimes on social media as an aggravating factor when it comes to sentencing, regardless of whether post and boast laws existed. Offenders who champion their offending on social media were already likely to cop harsher sentences, especially considering such posts often feature in police briefs of evidence.

The proposed Western Australian laws are considered particularly problematic, because of the possibility they could be used to outlaw peaceful protest.

In a letter sent to the attorney general, Tony Buti, earlier this month, the Conservation Council of WA executive director, Matt Roberts, urged the government to make a carve-out in the laws protecting protest and satire.

“We understand the legislation is intended to deter the glorification of illegal activity on social media. We share the concerns of youth justice advocates and legal professionals who say the laws may have a disproportionate impact on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, particularly young people,” Roberts said in the letter.

“We are also concerned the legislation may unintentionally lead to the repression of peaceful, nonviolent protest, including for environmental causes.”

WA Justice Association co-founder Tom Penglis told the West Australian there was no evidence such laws reduced crime, saying “they’re based on ‘vibes’ not evidence”.

Sotiri, from the Justice Reform Initiative, agrees.

“It is a total fantasy to believe that threatening harsher penalties will deter children from offending … every jurisdiction that has taken this ‘tough on crime’ approach has seen the same result: higher incarceration rates, more children cycling in and out of harmful remand, and no long-term benefit to community safety.”